From Sugar to Spices: Slavery in Trinidad (Cuba), Charleston (U.S.), and Zanzibar (Tanzania)

Introduction

My travels took me from Trinidad, Cuba, to Charleston, South Carolina, and Zanzibar, Tanzania —three locations with a shared but geographically distant history of slavery. Though separated by oceans, each place played a critical role in the slave trade, and the legacy of slavery remains present in their cultural and historical landscapes. The feelings I had from my 2021 visit to Charleston and 2019 visit to Trinidad still resonate with me today, and when I found myself in Tanzania—originally for a week of volunteering and another week of sightseeing—I couldn’t help but confront the echoes of slavery once more.

Slavery in Trinidad, Cuba

In 2019, I visited Trinidad, Cuba, a city deeply connected to the transatlantic slave trade, especially in the context of sugar production. The region’s Valle de los Ingenios (Valley of the Sugar Mills) was a major center for sugar plantations, where enslaved Africans were forced to labor under brutal conditions. The wealth and architectural beauty that Trinidad is known for today were largely built on the backs of these enslaved people.

During my visit, I rented a bike from a local hotel owner and set off to explore the area. I had some knowledge of the Valle de los Ingenios, but as I biked through residential neighborhoods and followed street signs, I found myself navigating for hours through rural roads in the hot weather. It felt as if I was being drawn to explore the vast, open fields. After cycling for hours, I finally arrived at the Valle de los Ingenios, a place steeped in the history of the brutal sugar trade that I had been unknowingly tracing. I stood at a mirador (viewpoint) overlooking the sprawling plantation fields. As I gazed out at the vast, peaceful landscape, it was hard to ignore the contrast between the serene beauty of the present and the immense suffering that once took place here.

One interesting fact I learned during my visit was that enslaved Africans who arrived in Cuba were considered physically stronger than those who reached North America. The reasoning behind this, as explained to me, was due to the longer and more grueling sails across the Atlantic to the Caribbean. Those who survived the extended voyage were seen as being more resilient, though this idea highlights the dehumanizing way enslaved people were viewed as commodities based on their labor potential.

While exploring the region, I also visited the Museo Nacional de la Lucha Contra Bandidos in Trinidad, which touches upon the broader history of the area, including the impacts of slavery. The museum, housed in an old convent, primarily focuses on revolutionary history, but it also provides glimpses into the social and economic structures of Trinidad that were rooted in the exploitation of enslaved labor. The museum serves as a reminder of the intertwined histories of colonialism, revolution, and slavery that shaped the region.

Slavery in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston played a pivotal role in the transatlantic slave trade, acting as one of the main ports where enslaved Africans were brought to the Americas. In fact, approximately 40% of all enslaved Africans who were brought to North America passed through Charleston. Visiting the Old Slave Mart Museum, I was reminded of the brutal system that enslaved thousands of men, women, and children, whose labor built the economic foundation of the American South.

In the Atlantic slave trade, I learned that while European traders largely dominated the trafficking of enslaved Africans, there were also African intermediaries who played a role in capturing and selling fellow Africans. Some tribal leaders, royals, and local elites participated as mediators between European traders and the people they captured. This participation underscores the complex and often coercive dynamics of the global slave trade. It was a system of exploitation that reached across continents and involved a wide range of actors.

Charleston’s slave market was officially closed in 1865 with the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery in the United States. However, illegal trading and the exploitation of enslaved people continued in secret for some time afterward. The legacy of this trade still lingers in Charleston’s landscape, culture, and social dynamics.

I also learned that financial services were directly tied to the trade. In Charleston, it was possible to take out loans specifically for purchasing slaves, embedding the institution of slavery into the economic fabric of the city. Auctions were elaborate and carefully managed. A few days before the auction, sellers fed enslaved individuals well and applied oil to their skin to make them appear healthier and more appealing to potential buyers. Younger men, prized for their physical labor potential, fetched the highest prices at these auctions. Prices for a young man could range from hundreds to thousands of dollars, depending on their strength and capabilities.

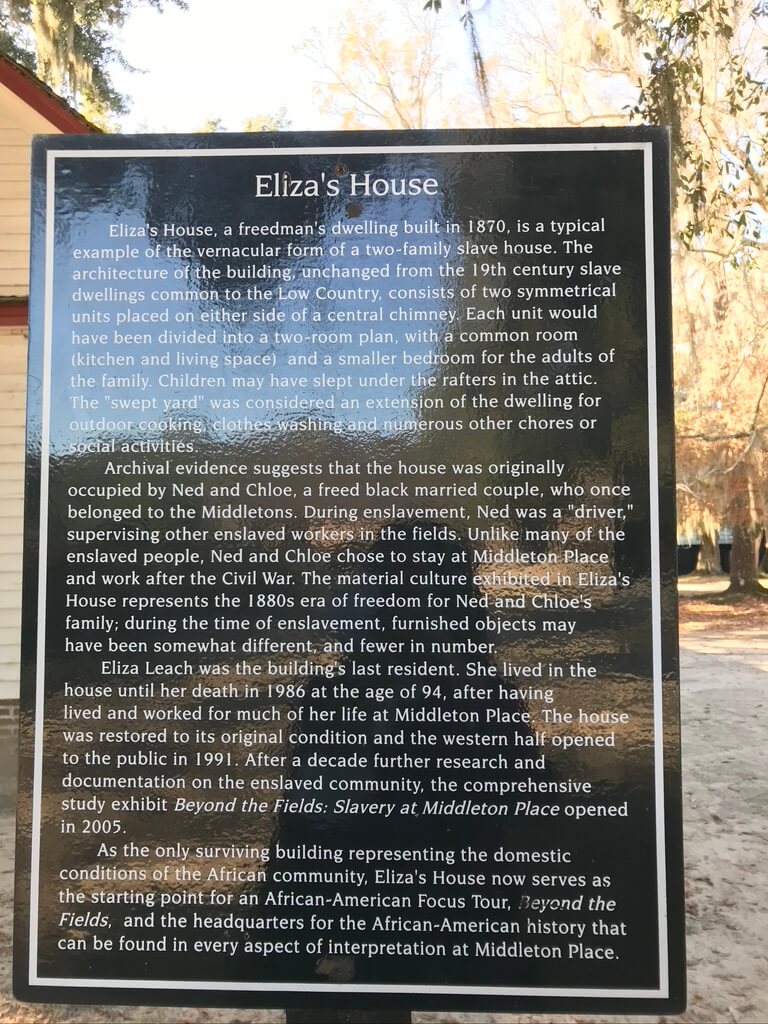

During my visit to Middleton Place, a former rice plantation, I learned more about the lives of enslaved Africans who worked the land. Interestingly, Middleton Place is unrelated to Kate Middleton, a fact the tour guide pointed out, as many visitors have asked about it. Unlike the harsher cotton plantations of the Deep South, rice plantations in South Carolina, like Middleton Place, offered some leniency. Once enslaved workers completed their daily quotas, they were sometimes allowed to return home earlier, a slight relief but far from an escape from exploitation. The wealth of the region was built on the backs of these enslaved people, who cultivated rice—known as “white gold”—that fueled the economy.

In Charleston, I also encountered unsettling experiences. As an Asian traveler, I noticed strange behaviors from some people—a subtle but palpable sense of discomfort, which reminded me that racism still lingers in the state. This was a stark contrast to the warm reception I received in Savannah, Georgia, where I felt welcomed and included. The difference between these two Southern cities left a lasting impact on me.

Slavery in Zanzibar, Tanzania

Zanzibar’s role in the Indian Ocean slave trade was pivotal. Unlike Charleston or Trinidad, which received enslaved people, Zanzibar was largely a point of departure—enslaved Africans were shipped to markets in the Middle East, Persia, and the Indian subcontinent. However, while many were transported elsewhere, a number of enslaved people remained in Zanzibar itself, forced to work in grueling conditions on the island’s spice plantations.

The Slave Market Memorial located at Christ Church Cathedral in Stone Town is a stark reminder of this dark history. Situated where slaves were once auctioned, the memorial now stands as a place of reflection and remembrance. Walking through the underground chambers where captives were held before being sold was a profoundly emotional experience, knowing that many of these individuals were torn from their homes and families, never to return.

In Zanzibar, much like in Charleston, prices for enslaved people were highest for young men, who were valued for their labor. Traders, including local African tribal leaders, royal figures, and mediators, often played a role in capturing and selling enslaved people to Arab and European buyers. The prices varied, but young, able-bodied men always commanded the highest price due to their capacity for intense physical labor. This disturbing reality reflected the global commodification of human beings for profit and power.

Though most enslaved people were exported to other regions, some were kept in Zanzibar to work on the island’s spice plantations. These individuals were forced to cultivate crops like cloves, vanilla, and cinnamon—luxury items that fueled Zanzibar’s economy and trade. The conditions on these plantations were harsh, with long hours and physical labor, and the lives of those who worked there were often marked by cruelty. The profits from the spice trade came at the cost of the suffering of these enslaved people.

The slave trade in Zanzibar was officially closed in 1873, when the British forced the Sultan of Zanzibar to sign a treaty banning the trade. However, like Charleston, illegal trading continued for years afterward, despite the official ban.

Related: Discovering Spice Farms of Zanzibar: A Journey Through Fragrant Fields

During my visit, I also learned about one of the most infamous figures of the Zanzibar slave trade: Tippu Tip. Tippu Tip was a powerful Swahili-Zanzibari trader and plantation owner who made his fortune through the slave and ivory trade. He captured and sold thousands of enslaved people from the interior of Africa to Arab and European traders. Tippu Tip’s role complicates the narrative of slavery in Zanzibar, as it highlights the uncomfortable truth that not all those involved in the slave trade were outsiders—some, like Tippu Tip, were African elites who profited from the suffering of others.

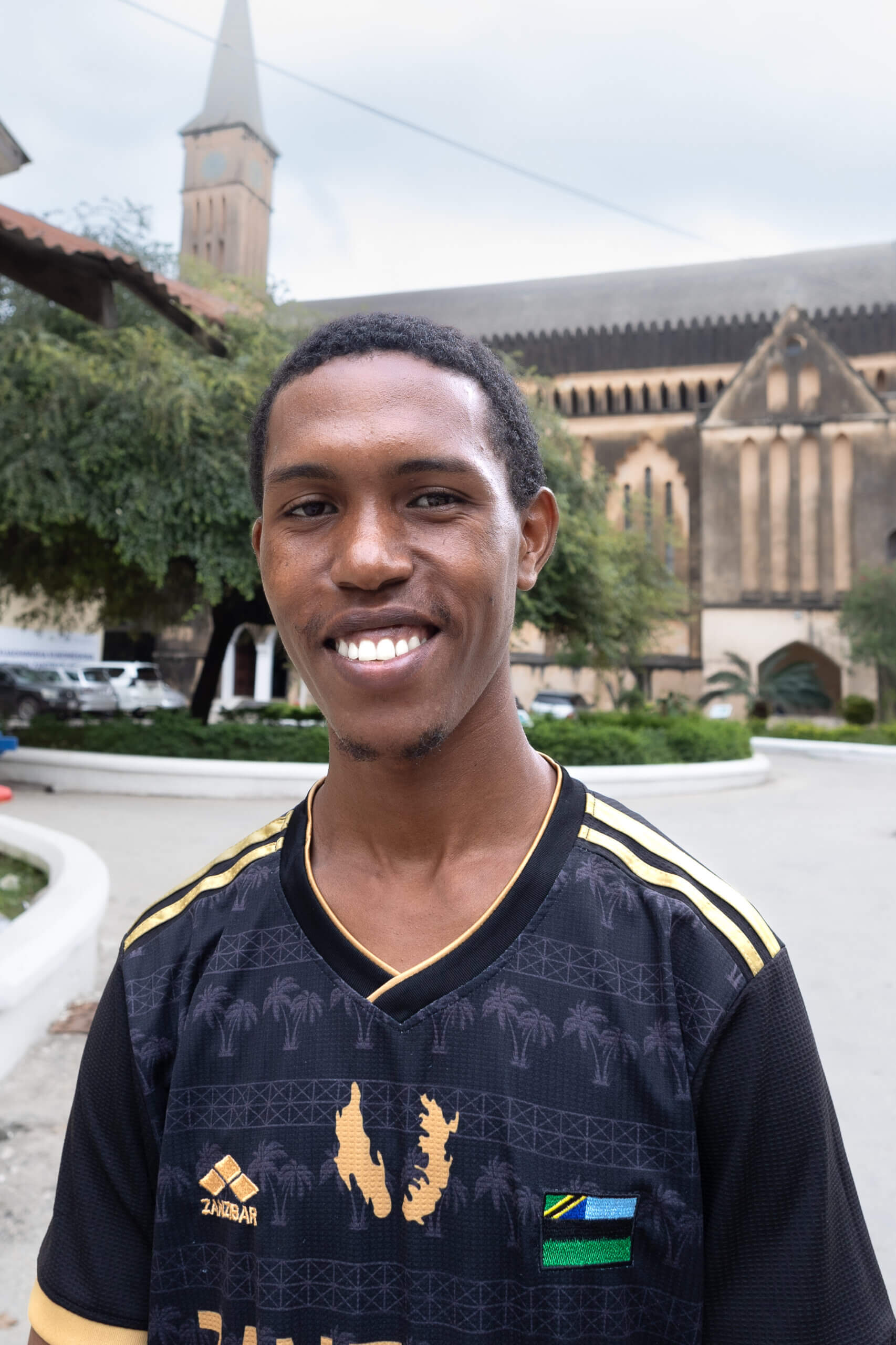

I asked my tour guide where the descendants of black authorities like Tippu Tip might be today, but he told me that I was only the second person to ask him that question, and no one knows for sure. The focus in Zanzibar is often on those who were enslaved, not those who participated in the trade. My guide, Sebastian, a university-educated Christian, shared his goal of establishing a music school to teach and empower young people. His enthusiasm and deep knowledge made it easier for me to ask difficult questions about this painful history.

While the tour was respectful and educational, I couldn’t help but notice a disturbing moment: groups of visitors posing for smiling photos in the chapel—built on the grounds of the old slave market—seemingly unaware or indifferent to the gravity of the place. It felt deeply unethical and disrespectful to witness such casual behavior in a place so closely tied to human suffering.

Comparing the Three Histories

Although Charleston, Zanzibar, and Trinidad participated in different slave trade routes—the Atlantic, Indian Ocean, and Caribbean—their histories share key similarities. All three locations were integral to the global system of forced labor and are haunted by the legacies of the slave trade. In Charleston, enslaved Africans brought expertise in rice cultivation, contributing to the region’s agricultural success. In Zanzibar, enslaved people worked under harsh conditions on spice plantations, producing cloves and vanilla that fueled the island’s economy. In Trinidad, enslaved Africans were forced to labor on sugar plantations, driving the wealth of the region.

The uncomfortable role of black authorities, such as Tippu Tip in Zanzibar, and other intermediaries complicates the narrative of slavery. While some free black individuals existed, most black people in Charleston, Zanzibar, and Trinidad trace their ancestry to those who were enslaved, and the history of those who profited from the trade is often left unspoken.

Reflections on Visiting These Sites

My journey through Charleston, Trinidad, and Zanzibar was a journey through time, into the painful realities of global slavery. These places left me with a deep sense of the past’s hold on the present. The racism I experienced in South Carolina was a reminder that the legacies of slavery persist, even today. On the other side of the world, in Zanzibar, the physical remnants of the slave trade—like the underground chambers—are still part of the island’s story, despite efforts to move forward.

While in Zanzibar, I had a poignant conversation with a local woman who expressed feeling left behind. She observed that descendants of enslaved people in the United States are often in much better economic positions today compared to many people who remained in Africa. Her comment added another layer to my understanding of the lasting effects of slavery, colonialism, and global inequality. It served as a reminder that while some descendants of the enslaved in places like the U.S. have gained opportunities through generations of struggle, many others in Africa continue to face systemic disadvantages, poverty, and exclusion.

Yet, amid the painful history, I found resilience. The descendants of the enslaved in Charleston’s Gullah Geechee culture and the rich Swahili traditions of Zanzibar both stand as symbols of cultural survival. These peoples endured unimaginable hardship, yet their cultures, languages, and traditions continue to thrive, demonstrating that survival against all odds is a form of resistance in itself.

Conclusion

My visits to Charleston, Trinidad, and Zanzibar have deepened my understanding of slavery’s global reach and its enduring impact on the present. From the rice plantations of South Carolina to the sugar fields of Trinidad and the spice farms of Zanzibar, the legacy of slavery cannot be ignored. It is a story of exploitation and suffering, but also one of resilience and survival.

The difficult questions I asked, the complex histories I encountered, and the contrasting behaviors of people in these spaces all remind me that the past is never truly behind us—it continues to shape how we see the world and each other. This journey reinforced for me that the global history of slavery is not just a story of human exploitation, but also a testament to the resilience of those who were oppressed and to the ongoing work needed to address its far-reaching consequences.

Reference

- Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Charleston Slave Trade. Retrieved from https://www.gilderlehrman.org.

- Joyner, C. (1984). Down by the Riverside: A South Carolina Slave Community. University of Illinois Press.

- Sheriff, A. (1987). Slaves, Spices, and Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire into the World Economy, 1770-1873. James Currey Publishers.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Valle de los Ingenios. Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org.

- Gray, J. M. (1960). Tippu Tip and the East African Slave Trade. Oxford University Press.

0 Comments